The Národ Lodge (among other Lodges) became dormant for the first time on October 14, 1938.

Many Masons emigrated after this date. From the aspect of historical continuity, it is important to mention the activity of about 50 active Brethren from various Lodges contributing to Masonic works in London. Some of them were members of the Czechoslovak Government in exile (Ladislav Feierabend, Jan Masaryk, Jaromír Nečas, Hubert Ripka) as well as members of the ministries in exile (František Uhlíř, Jaroslav Císař, František Černý, Ladislav Ploskal, Otta Dvouletý, Hugo Stein). Thanks to their diligence, Vladimír Klecanda was elected the Grand Master of the National Grand Lodge of Czechoslovakia in exile (NVLČs in exile). It was consecrated in the premises of the United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) on June 7, 1941. Hereby, the UGLE made an exception in permitting other Grand Lodge to operate in its territory. The UGLE even bestowed its premises in the Freemasons’ Hall in London. In March 1945, NVČLs in exile received a permission from the UGLE to continue its Masonic activities in London until the restoration of the NVLČs in Czechoslovakia.

The first preparatory Masonic meetings were held in Prague after the end of World War II. On May 11, 1946, Brethren from various Lodges, including the Národ Lodge, gathered during the Constituent Assembly of the Preparatory Committee of NVLČs. They sent letters to all Masters of active Lodges before 1938 in which they called for the reactivation of all Masonic activities. However, the exile Komenský Lodge (Comenius) already formally existed in Prague with the UGLE’s permission, in parallel with the existence of a government regulation addresed to the Minister of Interior Nosek, not to allow the restoration of Masonic associations. At the end of 1946, the Preparatory Committee wrote a comprehensive memorandum about Freemasonry in Czechoslovakia for the prime minister Gottwald and Ministers of Interior and Education. The Ministry of Interior elaborated a range of assessments. At the end, the permission to the renewal of Masonry and the existence of the NVLČs was given under certain conditions in 1947.

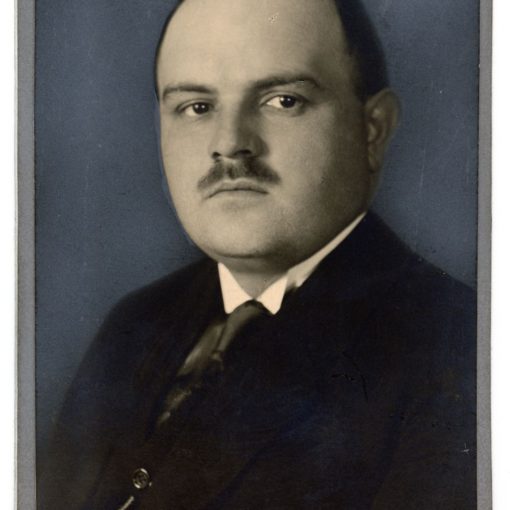

The conditions were outrageous and thus Freemasons negotiated for a long time to accept them. On October 26, 1947, the General Assembly was summoned to the Prague Colloredo-Mansfeld Palace. Bohumil Vančura was nominated and elected as Grand Master and Jaroslav Kvapil as Honourable Grand Master. Jiří Syllaba from the Národ Lodge was also elected to a high Office.

Masonic activities of individual Lodges were planned to be renewed step by step. However, since the very beginning, Masons had to cope with various problems. They searched for suitable premises, confiscated belongings, books, etc.

The conditions for the existence worsened more and more from 1948. The Communist Party asked for more difficult conditions, such as the presence of the Communist Party official at Lodge Ceremonies, transparency of the agenda of Lodges and even inclusions of women to the Order.

Since 1948, the situation among Masons was very uneasy. At the beginning, they all thought that it is only a transition period which can be overcome. Nevertheless, more and more Brethren leaned towards an idea to end their activities withthe increasing repression and strength of the communist dictatorship. On April 1, 1951, the General Assembly declared voluntarily Masonic activities temporarily dormant. Nobody thought that this would last till 1990.

Brethren continued with occasional secret meetings in their apartments. Outside Prague, there were two places for more frequent gatherings – Mariánské Lázně and Pastviny v Orlických Horách. The Brethren shared some philosophical reasonings there and they also tried to maintain contact with foreign Lodges. All Lodges in exile worked actively, too. In the totalitarian period, Brethren also helped each other materially, supported families of the Brethren affected by the repressions of the communist regime. Despite the inability to share the Masonic teaching within a Lodge, Brethren tried to apply Masonic ideas in their civil lives.